- About

- Future Students

- Academics

Academic Resources

- Current Students

My MHU ToolsAdult & Graduate Studies

- Athletics

- Alumni / Give

Bascom Lamar Lunsford

MHU’s Lunsford Festival was started in 1968 by Ed Howard, a pharmacist and jazz musician who knew Bascom Lamar Lunsford. Howard was enamored of the music he heard at Lunsford’s Mountain Dance and Folk Festival and wanted to start another festival honoring the music and musicians who played it at the place where Lunsford was born. Next to Lunsford’s own Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, it is the second-longest-running folk festival in western North Carolina.

Lunsford was responsible for preserving a great deal of music and dance in Southern Appalachia. His vast preservation efforts include two memory collection recordings for Columbia University (1935) and the Library of Congress (1949) – each comprised of over 300 songs, tunes, and games; commercial recordings; founding the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in 1928; founding, directing, and advising several other music festivals; fostering and encouraging musicians; performing; collecting dance figures; and a collection of the texts for thousands of songs and ballads. That collection is now housed, along with letters, newspaper clippings, a scrapbook, and other ephemera, in the Southern Appalachian Archives at Mars Hill University.

Though music and dance in Southern Appalachia during the late 18th to early 20th centuries was a mélange of West African, Native American, and European musical influences and was performed by music-loving people of many races and ethnicities, it came to be categorized along largely racial lines – especially in the late 19th and early 20th century folk revival movement and commercial recording industry. “Mountain music” and square dance traditions came to be associated with European Americans; spirituals, blues, and jazz with African Americans. Lunsford’s collections and festivals, which were undertaken in the Jim Crow South, clearly reflected these divisions and predominantly (though not exclusively) featured white people. Likewise, the materials in his collections also reflect the wider culture of the day and include ballads, religious songs, spirituals, pop and commercial music, as well as minstrel songs – many of which include racist images and language.

Through our programming, the Ramsey Center hopes to be part of the larger regional and national conversations going on now in the traditional music world – conversations that seek to tell an ever-fuller story of the music of Southern Appalachia in all of its diversity and complexity and to explore the cultural forces that helped to shape the Southern Appalachian region.

Bascom Lamar Lunsford: A Brief Biography

Bascom Lamar Lunsford was born in 1882 on the campus of Mars Hill University (then College), where his father taught. He grew up ensconced in the rural agricultural life of western North Carolina in a family that highly valued education. Traditional music was a large part of the backdrop of his early life. In addition to hearing music in the wider community, his maternal great-uncle Os Deaver was a renowned fiddle player and his mother sang ballads. Lunsford himself began playing music as a child, first on a cigar box fiddle and then a store-bought fiddle, which was joined by a banjo in his teens.

For much of his adult life, Lunsford lived on a farm in South Turkey Creek in the Leicester section of Buncombe County. He had an astonishing number of professions. A partial list includes:

- Nursery fruit tree salesman

- Bee and honey promoter

- Supervisor at the School for the Deaf in Morganton, NC

- Lawyer

- College professor of English and History

- Newspaper editor and publisher.

But, of all his professions, his great love – and what he referred to as his calling – was the music and dance of the Southern Appalachian Mountains.

Lunsford lived a rather extraordinary life that lasted 91 years and included two long marriages, seven children, being mentored by Robert Winslow Gordon, recording for Frank C. Brown, performing for the Roosevelts and the King and Queen of England, and working for the Works Progress Administration. He had close professional relationships with influential figures like Sarah Gertrude Knott, Sam Queen, and Samantha Bumgarner, among others. Lunsford was also active in politics throughout his life, and, like his collecting, his political and civic life reflected the racial divisions and political tensions of the 20th century. He worked with the southern Democratic Party into the 1960s: on political campaigns, as a candidate for State Senate, and as a reading clerk for the State House of Representatives.

For Further Reading

- Giddens, Rhiannon. Keynote Address for the IBMA Business Conference. 2017.

- Jamison, Phil. Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. (University of Illinois Press, 2015.)

- Jones, Loyal. Minstrel of the Appalachians. (The University Press of Kentucky, 1984.)

- Miller, Karl Hagstrom. Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow. (Duke University Press, 2010.)

- Pecknold, Diane, editor. Hidden in the Mix. (Duke University Press, 2013.)

- Whisnant, David. All That is Native and Fine. (University of North Carolina Press, 1983.)

- Winans, Robert B., editor. Banjo Roots and Branches. (University of Illinois Press, 2018.)

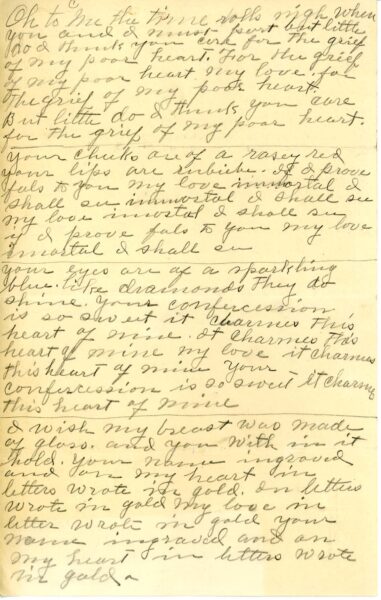

Lunsford was keenly aware of media stereotypes of southern Appalachia and in his work he aimed to portray the music of the mountains in a dignified manner. (Image from Bascom Lamar Lunsford Scrapbook, Southern Appalachian Archives, Mars Hill University.)

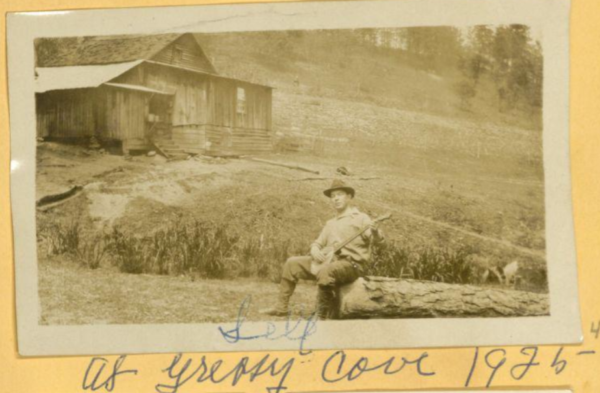

From left to right: Lunsford (fiddle), Mr. and Mrs. Lyda Brooks (guitar and banjo), and Gaither Robinson (banjo). (Image courtesy of the Bascom Lamar Lunsford Scrapbook, Southern Appalachian Archives, Mars Hill University.)

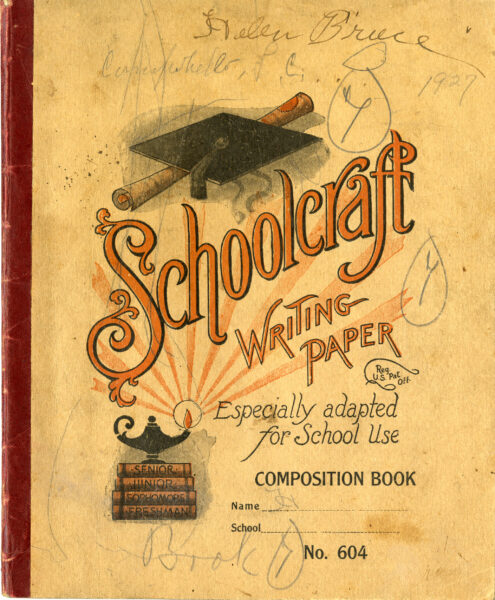

Lunsford collected many notebooks from school children filled with ballads and songs. (Image from Bascom Lamar Lunsford Collection, Southern Appalachian Archives, Mars Hill University.)